By Scott Quintavalle, Vice-President Systems Engineering , Tait Communications.

When Public Safety radio networks were analog, life was a lot simpler. There was little variation in the way audio was delivered, and measuring signal strength was a reasonable indication of audio quality for radio users, so long as there was not too much environmental noise or interference.

When Public Safety radio networks were analog, life was a lot simpler. There was little variation in the way audio was delivered, and measuring signal strength was a reasonable indication of audio quality for radio users, so long as there was not too much environmental noise or interference.

While digital radio undoubtedly delivers a host of benefits, it does cause a few headaches for technical and operations people who need to define and maintain a level of audio quality. Open standards like P25 bring many advantages in terms of consistency and interoperability. Unfortunately, digital receiver performance differs between manufacturers, because different receiver implementation results in sensitivity variations.

The bottom line: purely technical measures of audio quality are no longer sufficient in today’s highly-regulated environments, because high signal strength does not necessarily deliver high audio quality.

To provide a consistent, repeatable, user-centric measurement of audio quality, the TIA (Telecommunications Industry Association) has selected an existing subjective performance scale, against which digital radio networks can be measured. Rather than measuring technical criteria, it is focused on the radio user’s tolerance of acceptable interference and intelligibility. This measure is Delivered Audio Quality (DAQ).

In Public Safety applications in particular, DAQ is an important criterion against which your network is measured. Typically, coverage reliability will be expressed as “at least X DAQ with Y% reliability.” For example, DAQ 3.4 with 95% reliability is a common specification. This means that for 95% of coverage area, speech is “understandable without repetition. Some noise or distortion present”.

| Defining DAQ | |

| DAQ 1: | Unusable. Speech present but not understandable. |

| DAQ 2: | Speech understandable with considerable effort. Requires frequent repetition due to noise or distortion. |

| DAQ 3: | Speech understandable with slight effort. Requires occasional repetition due to noise or distortion. |

| DAQ 3.4: | Speech understandable without repetition. Some noise or distortion present. |

| DAQ 4: | Speech easily understandable. Little noise or distortion. |

| DAQ 4.5: | Speech easily understandable. Rare noise or distortion. |

| DAQ 5: | Perfect. No distortion or noise discernible |

Prioritising your outcomes to specify DAQ

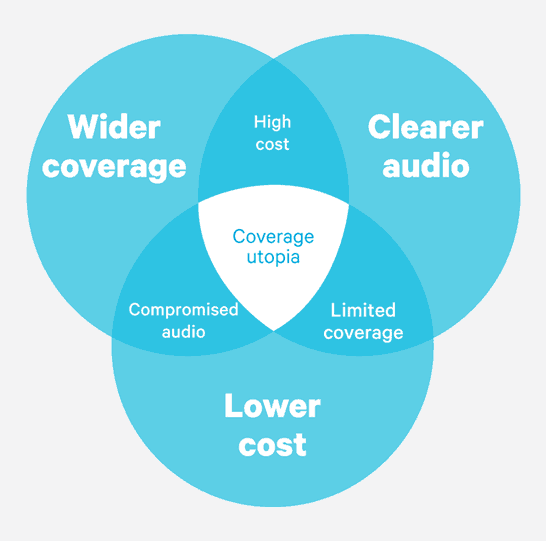

Deciding on appropriate DAQs for a network presents a conundrum, illustrated by this diagram. Essentially, there are three desirable outcomes that the network operator must prioritize carefully, because it is only possible to deliver two of them. These are:

Deciding on appropriate DAQs for a network presents a conundrum, illustrated by this diagram. Essentially, there are three desirable outcomes that the network operator must prioritize carefully, because it is only possible to deliver two of them. These are:

- Clearer audio

- Wider coverage

- Lower cost

The “sweet spot” of Coverage Utopia, is exactly that — unachievable. You will need to work closely with your network provider to be sure your network design and coverage plan reflect your priorities accurately.

Comparing DAQ with other quality measures

Generally, engineers are more familiar with technical measures and it should be said that DAQ is in no way intended to replace these:

- RSSI (Received Signal Strength Indicator)

- SiNAD (Signal-to-Noise and Distortion)

- BER (Bit Error Rate) and FER (Frame Error Rate)

Rather, DAQ will provide an additional tool to incorporate user experience into the measurement mix.

From an engineering perspective, these all remain valid, when designing network coverage, testing and troubleshooting issues and maintaining service levels. However, none of them can accurately and consistently reflect the experience of the radio user.

When officers call for backup, can they be heard clearly? Will they be understood? Will your comms centre have to repeat questions or commands? The reality of critical communications is that any delay is at best inefficient — at worst, deadly.

Specifying more than one DAQ

Another challenge you face when specifying—or delivering—DAQ is the power differential between mobile and portable radios. This sometimes leads to tender specifications with two different DAQs, for the different terminals. However, this is generally unnecessary, as a specified DAQ is always the acceptable minimum, regardless of the radio type, model or technology. There are likely to be areas where the specification is exceeded, but the minimum is never compromised. When defining how they will verify the specified coverage, your network provider will consider the type and model of radio they will use for testing.

Specifying multiple DAQs is justified however, for the differing needs in different regions across your coverage area. For example, inaccessible areas of your jurisdiction, where there are few roads and low population density, may justify a lower DAQ to reduce the cost of infrastructure. Meanwhile in the town, where officers are more likely to be deployed, they may need better audio quality to compensate for the noisier environment they are working in. Conversely, the risks associated with isolation in the less accessible areas might indicate a greater need than in the town. These are questions for you and your communications advisors to answer.

Is it too subjective?

While its critics claim that DAQ is too subjective, it gets right down to business—the reason your network exists—to provide critical communications for officers and front line workers. It gives your network provider a clear and agreed level of service that they must achieve.

The standard does not define terms such as “frequent”, “occasional” or “rare”. For example, to one user, “frequent” may mean 40% of the time. To another, it may be 20%. This is an accurate recording of individual tolerance, which may alter with circumstance, but not as useful as a measure of quality. Compounding that, frequency of interference or distortion in this context does not indicate or suggest how the interference occurs—clustered, or spread over time? Traditional audio quality measures still have a place for this kind of diagnosis.

Nevertheless, these subjective variations may also add a level of meaning. They do reflect tolerance or annoyance levels of individual people at the front line.

Summing up

In the critical communications environment, what matters is that those voice communications are heard and understood. DAQ is another tool that experts can use to design, measure and test how well your network achieves this.

This article is taken from Connection Magazine, Edition 3. Connection is a collection of educational and thought-leading articles focusing on critical communications, wireless and radio technology.

This article is taken from Connection Magazine, Edition 3. Connection is a collection of educational and thought-leading articles focusing on critical communications, wireless and radio technology.

Share your views, comments and suggestions in the Tait Connection Magazine LinkedIn group.

Issue: For large coverage test programs, it is time-consuming (more $$) to complete coverage testing entirely with subjective tests.

Alternatively, have you thought to use subjective testing with the user to determine a user-specific BER relative to their perceived DAQ. The new BER would relate to a CINR and then provide input to coverage modelling. The users can choose different methods of test: 1. complete subjective tests; 2. subjective tests to baseline BER for the user, and then agreement on new coverage modelling; 3. subjective tests to baseline BER for the user, then use BER-based coverage testing. The method of test would depend on how much time and money the user was willing to invest.

Suppose we could also take TSB-88’s DAQ to BER charts at face value, but judging from your article, they may not reflect the user experience.

Yes, Matt, cost can be a major consideration in an end-user deciding whether or not to specify a subjective assessment of the performance of their network or a more cost-effective test using an objective metric such as BER.

We’ve found that for the purposes of coverage testing of digital systems at least the mapping between DAQ and BER suggested by TSB-88 correlate fairly well with the user experience and subjective rating. When the evaluation team is played audio recorded from terminals operating at specific bit error rates under the conditions typically present during a coverage verification test, the mean of the distribution of scores line up pretty well with that suggested by the TIA in TSB-88. As such we’ve never had to deviate from these recommendations. This type of process can help an end user decide if the extra cost of a full subjective evaluation is really worth it or if they have the confidence that an objective measure such as BER will suffice for proof of the coverage performance of their network.

The Delivered Audio Quality (DAQ) scale is derived from the early radio CM (“Circuit Merit”) system. While that 0-5 scale is sensible in analog systems, it is much less descriptive in the world of digital radio systems. Digital systems either provide acceptable service (e.g. 3.0 DAQ or better) or inadequate service (DAQ typically 2.0 or poorer). Way too much effort is expended trying to distinguish between DAQ of 3.0 and 3.4 or trying to define the difference between frequent repetition and occasional repetition or between little and rare noise and or distortion.

What the radio system design and measurement world needs is a measurement system that can measure and describe digital response. In keeping with the binary basis of digital equipment, perhaps a system of 0 (message failed) and 1 (message succeeded) would be a starting place. This simpler scale would have benefits not only in digital voice testing but also in digital data traffic where retries and forward error correction are all common approaches to improve the communications stream.

Yes, Mike, I agree that effective evaluation of voice quality on a digital wireless system is definitely an area for additional research. In addition, consideration needs to be given to whether one particular type of rating is more useful for detailed evaluation and comparisons of vocoders in controlled environments versus the subjective evaluation that takes place in the field when determining the coverage performance of a network.